Your credit score follows you everywhere—from apartment applications to car loans to mortgage approvals. But have you ever wondered what actually creates that three-digit number that holds so much power over your financial opportunities? The answer lies in your consumer credit files, complex documents that most people never see but that quietly shape their entire financial future. These files contain far more than just payment history, and understanding their hidden complexities can mean the difference between approval and rejection, between premium rates and subprime penalties.

What makes this particularly challenging is that identical financial behavior can produce surprisingly different credit profiles across the three major bureaus. Minor inaccuracies you’re unaware of could be costing you thousands in higher interest rates, while systematic errors in data processing create obstacles that seem impossible to overcome. The role of consumer credit files in shaping your score involves intricate algorithms, timing mechanisms, and data weighting systems that most consumers never learn about—yet mastering these elements can unlock financial opportunities you didn’t even know existed.

How Credit Files Transform Raw Data Into Your Financial Profile

Your credit file operates as a complex data ecosystem where information from dozens of sources converges to create your financial identity. The three major credit bureaus—Experian, Equifax, and TransUnion—each maintain separate databases that process millions of data points daily. Understanding the role of consumer credit files reveals how this seemingly straightforward system contains intricate mechanisms that can produce surprisingly different credit profiles for the same individual.

The data aggregation process begins when creditors, known as data furnishers, submit account information to the bureaus on varying schedules. Some lenders report monthly, others quarterly, and many choose to report to only one or two bureaus rather than all three. This selective reporting creates the foundation for discrepancies that can significantly impact your score across bureaus. The role of consumer credit files becomes clear here, as even small timing differences—such as a $500 balance reported to one bureau but not another—can alter utilization ratios and affect scores.

The weighting algorithms that determine which data elements receive priority in your credit file compilation operate on sophisticated statistical models. Employment history, for instance, doesn’t directly influence your score, but it serves as a verification tool for validating other data points. When employment conflicts exist, the role of consumer credit files is to trigger additional verification protocols that can delay or complicate updates to more critical financial information.

Address changes create particularly complex scenarios within credit file architecture. Each address in your credit file serves as an anchor point for associating accounts and inquiries with your identity. When you move frequently or maintain multiple addresses, the bureaus’ matching algorithms must determine which accounts truly belong to you. The role of consumer credit files in this process is critical, as occasional errors can lead to mixed files or the omission of legitimate accounts.

The temporal aspects of credit file updates reveal another layer of complexity. Account status changes don’t appear instantly across all bureaus, and the timing of updates can create windows where your file presents an inaccurate financial picture. A loan marked paid off on one bureau may still show a balance on another, confusing lenders and delaying approvals. This demonstrates once again the essential role of consumer credit files in shaping both your creditworthiness and access to financial opportunities.

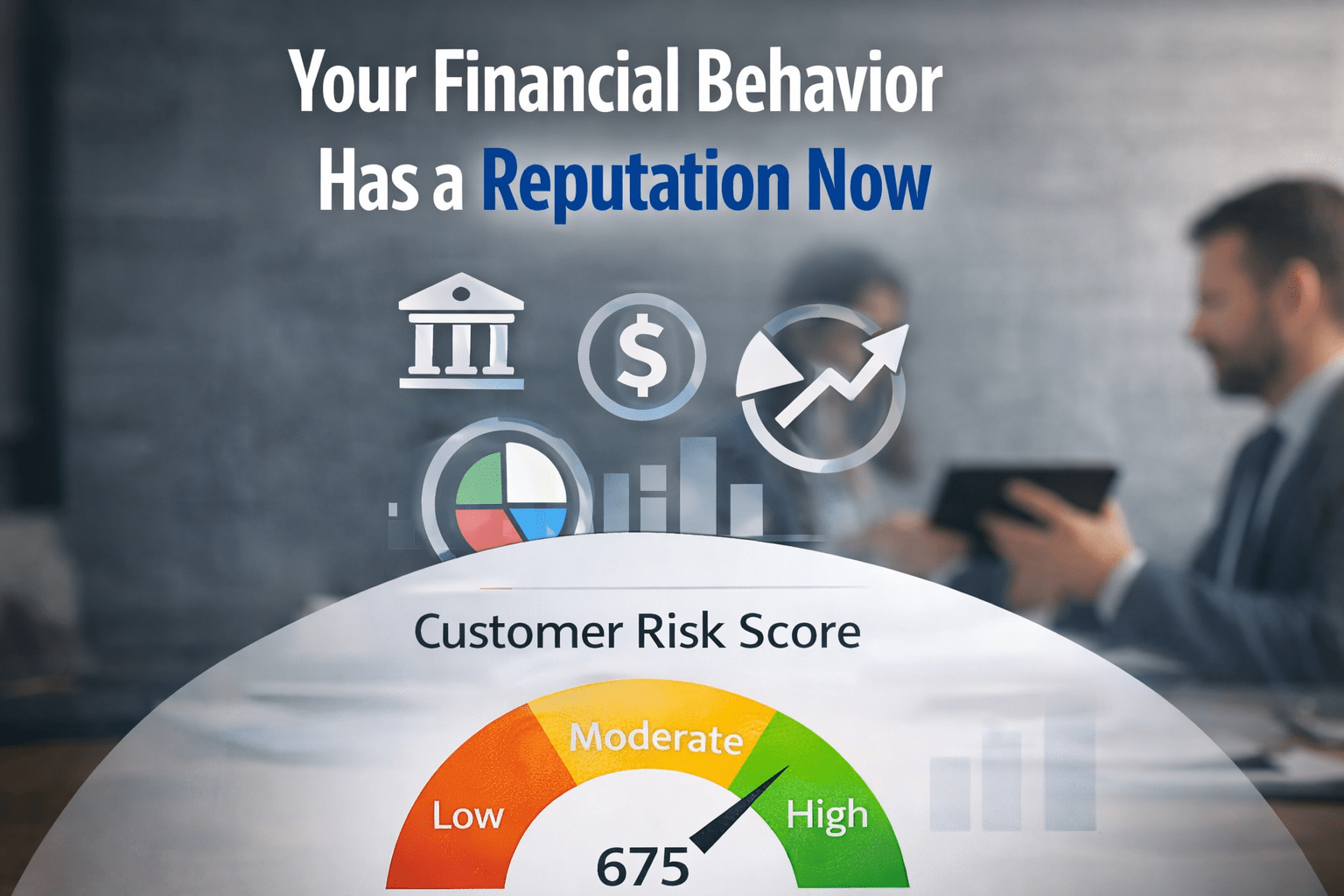

Where Your File Data Becomes Your Financial Reputation

Credit score calculation extends far beyond the basic percentages most consumers understand, incorporating sophisticated weighted formulas that analyze patterns within your credit file data. Payment history, while representing 35% of your FICO score, doesn’t treat all payments equally—the algorithm considers account type, severity of lateness, frequency, and recency. A single 30-day late payment on a mortgage carries more weight than the same lateness on a retail card. Here, the role of consumer credit files is evident in shaping how lenders interpret these differences.

The credit utilization ratio calculation demonstrates the nuanced approach credit scoring takes toward your credit file information. Rather than simply dividing balances by total credit limits, the algorithm examines individual account utilization and overall trends. An account with zero balance contributes differently than one at 5% utilization. These patterns highlight the role of consumer credit files in recognizing not just balances but behaviors over time.

Closed accounts with positive history add complexity to score calculation. Conventional wisdom suggests keeping accounts open to preserve history length, but the reality is more layered. Closed accounts still count toward history length for up to 10 years but no longer impact utilization ratios. This means closing accounts can immediately raise utilization and reduce scores. Understanding this interplay shows the role of consumer credit files in balancing history against utilization.

The cascading impact of single inaccuracies reveals how interconnected credit file elements affect your score. An incorrectly reported late payment doesn’t just harm your payment history—it can influence your credit mix and risk profile. When inconsistencies appear, scoring algorithms may apply additional scrutiny, lowering your score further. These scenarios emphasize the critical role of consumer credit files in maintaining accuracy across all reporting categories.

Score variations across different scoring models reflect the diverse ways your credit file data is interpreted. FICO 8, FICO 9, and VantageScore 3.0 each apply unique weighting methods to identical data, creating variations of 50 points or more. These differences are especially pronounced when your file contains unique elements like medical debt or paid collections. Once again, the role of consumer credit files explains why identical behaviors can produce dramatically different outcomes across scoring models.

Identifying and Understanding Systemic Credit File Inaccuracies

Credit file errors follow predictable patterns that reflect weaknesses in the automated systems processing millions of data points monthly. Identity mixing represents one of the most complex error categories, occurring when the bureaus’ algorithms incorrectly associate accounts with your credit file. This issue highlights the role of consumer credit files in determining how personal data is matched and how easily misidentifications can create lasting financial consequences.

The automated data processing systems that manage credit file updates rely on speed-focused matching algorithms that create recurring inaccuracies. When creditors submit batch updates, records are assigned based on combinations of name, address, and Social Security number. Even small formatting variations can result in mismatched assignments. The role of consumer credit files here shows how system vulnerabilities, rather than consumer behavior, often drive persistent errors.

Medical debt reporting creates one of the most error-prone categories in credit files. Accounts often change hands multiple times—from providers to billing companies to collectors—creating opportunities for distortion. Incorrect balances, statuses, or responsible party details often result. The role of consumer credit files becomes clear in these cases, as inaccurate medical debt reporting can severely damage a consumer’s score despite not reflecting reality.

Account status misreporting represents another systematic error that heavily impacts credit scores. The difference between “current” and “30 days past due” status carries significant weight, yet automated systems sometimes fail to reflect payment updates. Such mistakes illustrate how the role of consumer credit files directly influences scoring models and can cause disproportionate harm from small reporting oversights.

The phenomenon of “zombie debts”—settled or discharged accounts that reappear—shows another weakness in the system. When discharge data doesn’t propagate correctly, old debts resurface with incorrect balances or statuses, often years after resolution. These reappearances emphasize once again the critical role of consumer credit files in shaping financial opportunities, as even resolved debts can reemerge to derail new applications.

Common Credit File Error Categories:

- Identity mixing errors affecting 15-20% of credit files annually

- Account status misreporting, particularly current vs. delinquent classifications

- Duplicate account listings from creditor system migrations

- Incorrect balance reporting due to automated processing delays

- Mixed file errors where accounts from other consumers appear

- Outdated personal information affecting account verification processes

Advanced Techniques for Proactive Credit File Error Detection

Effective credit file monitoring requires systematic approaches that extend beyond the basic services most consumers employ. The optimal monitoring strategy involves staggered reviews across the three major bureaus, recognizing that each updates information on different schedules and may contain unique inaccuracies. Understanding the role of consumer credit files in this process ensures a continuous oversight cycle that captures errors closer to when they occur.

The dispute window timing represents a critical factor in successful error correction that most monitoring approaches overlook. Inaccuracies are easiest to resolve within 30–60 days of appearing, before they become embedded in multiple systems. Early detection through frequent monitoring highlights the role of consumer credit files in determining how quickly errors spread and how difficult they are to correct if ignored.

Advanced error detection techniques focus on identifying subtle data inconsistencies that automated monitoring often misses. These include variations in account opening dates, discrepancies in credit limits, and inconsistent payment histories across bureaus. Professionals analyzing these details can better understand the role of consumer credit files in exposing systematic processing flaws that require specialized correction.

Credit freeze strategies serve dual purposes in credit file management—preventing new inaccuracies while creating controlled environments to address existing errors. When files are frozen, new accounts and inquiries cannot be added, reducing error sources while you focus on corrections. This proves particularly valuable in cases of identity theft recovery or mixed file situations.

The documentation requirements for effective monitoring extend beyond error identification to include detailed logs of changes, bureau correspondence, and dispute evidence. Proper record-keeping ensures persistence in resolving recurring issues and provides a foundation for professional intervention if needed.

When DIY Credit Repair Efforts Require Expert Intervention

The complexity threshold for professional credit repair intervention typically emerges when consumers encounter systematic errors that resist standard dispute processes or when multiple inaccuracies create compounding effects on creditworthiness. Professional repair services understand the role of consumer credit files in shaping financial opportunities and apply specialized knowledge of bureau operations, creditor relationships, and legal frameworks that individuals cannot easily replicate.

Professional credit repair strategies extend beyond error identification to include sophisticated dispute techniques that leverage industry relationships and legal precedents. These professionals maintain ongoing communication with bureau personnel and understand the internal processes that determine how disputes are evaluated and resolved.

The legal frameworks governing credit file accuracy provide professional services with tools unavailable to individual consumers. The Fair Credit Billing Act establishes requirements for how bureaus must investigate disputes, but enforcing them often requires expert legal knowledge. Professionals can escalate disputes through legal channels when standard processes fail to resolve inaccuracies.

Complex issues like identity theft recovery and mixed file separation require specialized expertise that justifies professional intervention. These situations involve multiple layers of documentation, coordination with financial institutions, and fraud prevention protocols. Professional services possess the experience necessary to manage these cases efficiently.

The return on investment for professional credit repair services becomes clear when considering the financial benefits of improved credit files and scores. Lower interest rates, premium lending terms, and expanded opportunities all stem from accurate reporting. The role of consumer credit files here directly influences the options available to consumers preparing for major financial decisions such as home purchases or business financing.

Taking Control of Your Financial Future

Your credit file isn’t just a collection of data—it’s the foundation of your financial opportunities, and understanding its complexities gives you unprecedented control over your economic future. The intricate relationships between data aggregation, score calculation, and systematic error patterns reveal why identical financial behavior can produce vastly different outcomes across bureaus. These hidden mechanisms, from utilization weighting algorithms to identity mixing vulnerabilities, demonstrate that credit file management requires far more sophistication than most consumers realize.

The path forward involves recognizing that your three-digit credit score represents the culmination of countless data processing decisions, timing mechanisms, and algorithmic interpretations that operate largely outside public view. Whether through strategic monitoring techniques, professional intervention, or systematic error correction approaches, taking active control of your credit file transforms you from a passive recipient of algorithmic decisions into an informed participant in your financial destiny. The question isn’t whether credit file inaccuracies will affect you—it’s whether you’ll discover and correct them before they cost you thousands in higher interest rates and missed opportunities.